British Museum Etches Dürer’s ’Rhinoceros’ Into Bitcoin Blockchain—Art Meets Immutable Ledger

London’s British Museum just carved a 16th-century masterpiece into the digital age—by minting Albrecht Dürer’s iconic ’Rhinoceros’ woodcut as a Bitcoin Ordinal. No auction houses, no gallery markups—just pure, uncensorable art history on-chain.

Why Bitcoin? The museum’s move bypasses traditional art-market gatekeepers, slashing provenance disputes with cryptographic certainty. Each stroke of Dürer’s 1515 engraving now lives rent-free in the blockchain’s decentralized archive.

Meanwhile, Sotheby’s executives suddenly remember they forgot to buy Bitcoin in 2013. The rhinoceros, at least, won’t care about the next 20% crypto correction.

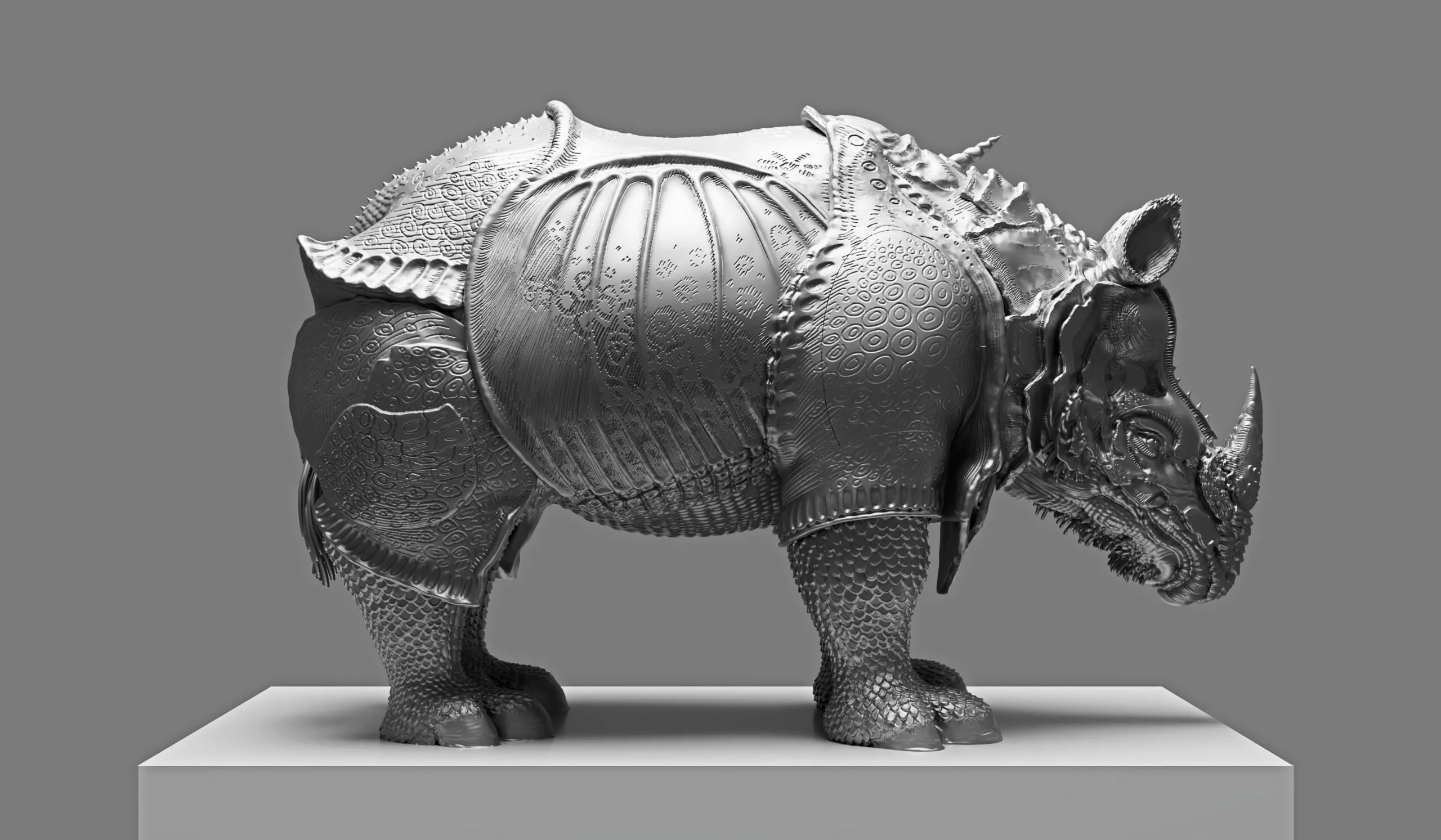

Asprey Studio’s Rhinoceros. Silver sculpture. Image: Asprey Studio

Asprey Studio’s Rhinoceros. Silver sculpture. Image: Asprey Studio

“It’s inscribed in Ordinals, in [a] full block,” Asprey Studio Chief Creative Officer Ali Walker told Decrypt. He explained that, “it’s a parent/child inscription, so the parents are Asprey Studio and the British Museum, and the child is the actual work.”

Buyers will receive the digital inscription first, said Walker, since it takes several months to make the silver sculpture, which is produced to order. Creating the 40cm solid silver sculptures was a challenge, he explained, because of the metal’s unique properties.

“We have digital sculptures at Asprey Studio,” he said. “So we first sculpted it digitally, and then we worked out how we cut it up into small, manageable pieces.” Those pieces are then welded together, a months-long process that “only a couple of people in the UK” can undertake, Walker said.

Dürer, artistic pioneer

Born in 1471, Albrecht Dürer was one of the pioneers of the German Renaissance, combining the emerging technology of printmaking with new discoveries in optics and anatomy to produce revolutionary works.

Dürer’s seminal “Rhinoceros” print was completed without the artist actually having seen a live rhino, instead basing his work on a description from a Portuguese merchant’s newsletter.

“In his time, he was so advanced,” Walker told Decrypt. “Not just as an artist; he was doing self portraits at a time when no one else was, he was doing wood block prints and he made money out of printing his own work.”

He was also an early adopter of modern branding, designing a monogram based on his initials that functioned as his own logo, and brought “the first art-specific intellectual property lawsuit in Venice,” according to “The Art of Forgery” author Noah Charney.

In one memorable screed, Dürer railed against printmakers who made unauthorized copies of his work, accusing the “pilferers of other men’s brains” of laying their “thievish hands upon my works.”

“Not only will your goods be confiscated,” Dürer warned the Renaissance IP thieves, “but your bodies also placed in mortal danger.”

Dürer, Walker suggested, WOULD be right at home in the modern art world, where digital artists use NFTs to establish provenance, and wrestle with the implications of AI on copyrighted works. “It’s fascinating,” he said, “and it kind of fits in with the whole digital inscription idea.”

Walker was at pains to stress that “Dürer’s drawing does not suddenly become an NFT just because it’s on the blockchain,” noting that, “We’re creating a whole new interpretation of the piece, and the original Dürer drawing of ’The Rhinoceros’ is actually owned by the museum.”

“It’s slightly different dynamics,” he said. “Digital art is the thing, and it’s basically just preserving the piece on the blockchain so it will last forever.”

The British Museum and Web3

For its part, the British Museum is no stranger to Web3 technology. Back in 2021, the venerable institution partnered with French startup LaCollection to launch a range of NFTs based on artworks from its collection, including Hokusai and Turner.

Two years later, it linked up with metaverse gaming platform The Sandbox, with plans to offer “new immersive experiences” alongside its own metaverse space in the online game world.

Edited by Andrew Hayward