Debt-Fueled Fortresses: How Land Barons Paved the Way for Bitcoin Treasury Strategies

For centuries, the ultra-wealthy have leveraged debt to amass imperishable assets—land, gold, and now digital gold.

From feudal estates to corporate balance sheets, hard assets have always been the ultimate store of value. They don't degrade, they can't be printed into oblivion, and they serve as the perfect collateral in a debt-based financial system.

Enter Bitcoin: the digital hard asset.

Public companies and nation-states now mimic ancient land barons by stacking SATs on their balance sheets. They issue cheap debt against appreciating crypto holdings—a move that would make any Renaissance banker nod in approval.

This isn't speculation—it's treasury management 3.0. While central banks play with fiat printers, smart money builds fortresses of encrypted value. The strategy bypasses traditional inflation hedges and cuts directly to the hardest money ever created.

Because let's be honest—if your CFO isn't considering Bitcoin, they're probably too busy optimizing their T-Bill yields to notice the entire monetary system shifting beneath their feet.

Historical Precedents of Leveraged Asset Wealth

The idea of using debt to acquire scarce assets isn’t theoretical; it’s been the foundation of some of the greatest fortunes in modern history. From real estate dynasties to industrial empires, the pattern repeats: smart leverage, hard assets, and favorable economic conditions often combine to create outsized wealth.

Donald Trump’s father is a textbook case of debt-powered real estate wealth. During the New Deal era, he tapped Federal Housing Administration (FHA) loans to build thousands of homes and apartments in New York’s outer boroughs. These government-backed mortgages let him expand far beyond what his own capital allowed. By the time Donald inherited the business, it was worth tens of millions — proof that FHA-subsidized debt had seeded a generational fortune.

Across Europe’s post-WWII boom, developers Leveraged cheap bank loans and credits to assemble massive property holdings. In West Germany, the Conle brothers built as many as 18,000 apartments during the 1950s “economic miracle”, much of it bank-financed. In the UK, developers rode a similar wave, borrowing to buy land in London and other cities just as property values took off. Many of today’s real estate dynasties were cemented in this period — by borrowing aggressively when money was cheap and growth was strong.

Hong Kong’s real estate moguls built empires by buying when others panicked. During crises like the 1965 bank crash and 1967 riots, entrepreneurs such as Li Ka-shing, Lee Shau Kee, and the Kwok family scooped up land at depressed prices — often with the help of bank loans or family credit. When Hong Kong’s economy surged in the following decades, that land became priceless. Their rise shows how credit plus courage in downturns can create fortunes that endure for generations.

Even in the modern era, the same playbook works. Nick and Christian Candy started in 1995 with a £6,000 loan from a relative to renovate a single flat. They reinvested profits, took on more financing, and eventually developed ultra-luxury projects like One Hyde Park. Within about a decade, they had executed roughly 50 leveraged real estate deals, amassing hundreds of millions. Their story is a reminder: debt-financed property plays are far from obsolete.

Perhaps the boldest example is Hugo Stinnes, the so-called “Inflation King.” As hyperinflation ravaged Germany, he borrowed heavily in rapidly devaluing paper marks and used the funds to buy mines, factories, and ships. When the currency collapsed, his debts evaporated in real terms, but his hard assets skyrocketed in value. In effect, Stinnes shorted the currency and went long on real assets — a daring leverage bet that made him the richest man in Germany.

Inflation as the Tailwind

What ties many of these stories together is inflation’s quiet magic. Rising prices not only boosted asset values but also eroded the real burden of debt. In the U.S., for instance, median home prices more than doubled in the inflationary 1970s, while fixed-rate mortgage payments shrank in real terms. Economists have noted that young households with mortgages were among inflation’s biggest winners — repaying yesterday’s debts with tomorrow’s cheaper dollars. Of course, leverage cuts both ways: borrowers can be wiped out if asset values collapse or deflation sets in. But history shows that, under the right conditions, debt-financed hard assets have repeatedly turned ordinary entrepreneurs into enduring dynasties.

Corporate Bitcoin Treasuries: The New Debt-Asset Play

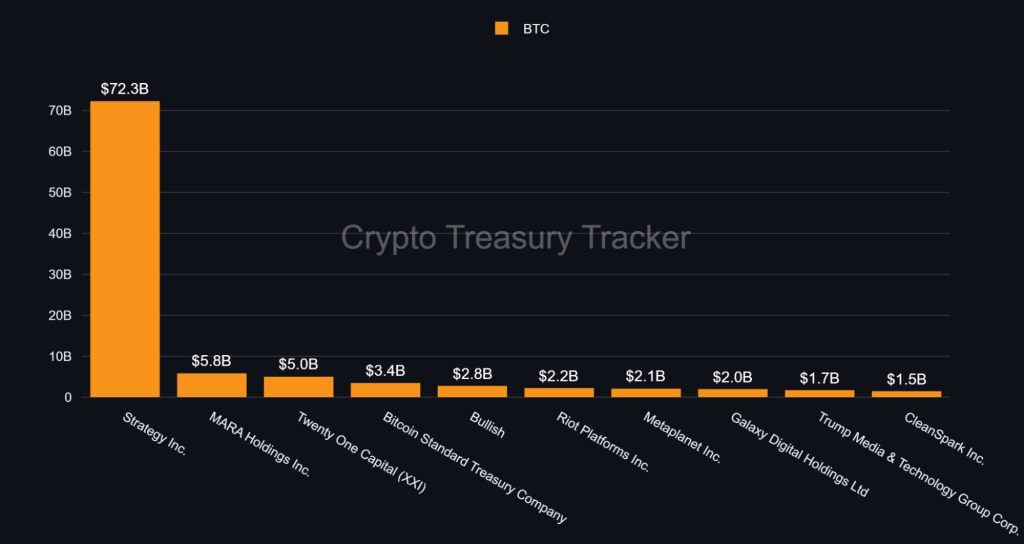

In recent years, a number of companies have started borrowing to buy Bitcoin — reviving the classic “debt for hard assets” playbook, but applying it to a digital frontier. Often called Bitcoin treasury companies, these firms raise capital through bonds, convertible notes, or equity offerings with the explicit goal of holding BTC as a primary reserve asset. We examined these companies in detail in our latest research report on Bitcoin treasuries, and collectively, private and public companies now hold an estimated.

Strategy (MSTR): The Poster Child

No company illustrates this approach better than Strategy. Beginning in 2020, CEO Michael Saylor reshaped the firm’s balance sheet by converting cash reserves into bitcoin and then repeatedly raising debt to buy more. As of August 2025, Strategy owns about. The company has issued convertible bonds and secured loans to finance these acquisitions, essentially mortgaging itself to buy hard assets, except the “land” is digital. Investors have so far rewarded the move, with Strategy’s stock price surging more than, representing a gain of.

Other Firms Following Suit

A growing number of companies across industries have adopted similar tactics. Bitcoin miners such as Marathon Digital Holdings and Riot Blockchain naturally accumulate BTC from operations, while others, including Tesla, Block (Square), Coinbase, GameStop, and Semler, have explicitly bought Bitcoin as a treasury reserve. Many of these purchases were funded through debt or equity offerings. For example, in 2025, GameStop announced that it would issue convertible notes to raise funds for buying crypto. Tesla made headlines in 2021 with a $1.5 billion Bitcoin purchase, funded from cash, and Block has likewise allocated part of its reserves to BTC. By 2025, Sentora Research counted at least, with combined holdings of $113,321,728,522 in August. What began with Strategy has now become a notable shift in corporate finance strategy.

The Rationale: Bitcoin as “Digital Gold”

The logic behind these moves closely resembles the thinking that once drove real estate and Gold acquisitions. Bitcoin’s capped supply of 21 million makes it a scarce, “hard” asset. In a climate of loose monetary policy, inflation fears, and geopolitical volatility, many CFOs view cash as a “melting ice cube” and prefer scarcer assets that can hold or increase value. The idea is that if fiat currency continues to lose purchasing power, Bitcoin’s price in fiat terms should rise, allowing debt to be repaid later with cheaper money. This mirrors the benefits enjoyed by homeowners and developers who borrowed against property during inflationary periods.

A Growing Corporate Model

For some companies, Bitcoin accumulation is no longer just a treasury allocation but a Core business model. Strategy itself has effectively become a hybrid software company and Bitcoin-holding vehicle. New firms and ETFs now exist solely to accumulate BTC as their asset base. The strategy has become mainstream enough that in 2024, accounting rules were updated to let companies mark Bitcoin assets to market, eliminating earlier reporting penalties. What began as a fringe experiment is now a legitimate topic in corporate boardrooms: should companies leverage debt not only to buy land and factories, but also Bitcoin?

Validity and Critical Comparison of the Analogy

The parallels between debt-financed real estate and corporate Bitcoin treasuries are striking. In both cases, the strategy is to borrow in a depreciating currency and acquire a scarce asset with the hope that inflation or debasement will tilt the equation in favor of the borrower. Historical examples from Fred TRUMP to Hugo Stinnes show how this playbook has, under the right conditions, created enduring fortunes. Bitcoin advocates see themselves as heirs to this tradition, executing the same “short fiat, long hard asset” trade—only with digital scarcity instead of land.

Yet the analogy has limits. Real estate offers utility, cash flow, and centuries of price history, while Bitcoin is newer, more volatile, and lacks inherent income to help service debt. Leverage magnifies both upside and downside, and unlike a landlord who can rely on rents, a Bitcoin-heavy company must cover interest from other operations or reserves. Regulatory uncertainty and public market scrutiny add further complications that previous generations of asset-leveraging families did not face.

The bottom line is that the comparison is valid in concept but riskier in execution. Bitcoin may indeed prove to be the “digital land” or “digital gold” of the 21st century, rewarding those who borrow to acquire it. Or it may become a cautionary tale of over-leveraged bets on an asset whose role in the financial system was still unproven. As history reminds us, debt is a powerful tool that can build dynasties—or destroy them. The eventual verdict on Bitcoin treasuries will depend not just on boldness, but on whether this modern asset can deliver the same resilience that land and property once did.

Disclaimer: The opinions in this article are the writer’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of Cryptonews.com. This article is meant to provide a broad perspective on its topic and should not be taken as professional advice.